Home » Uncategorized

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Eggstraordinary Art: A New Book Just Released on Egg Decorating

Once a year for at least a week, my kitchen and dining room become a frenzied artist’s workshop full of dyes, the smell of melting beeswax, and a variety of tools. I go on a hunt for white chicken eggs to ethnic shops (and chicken farms!) and buy as many as I can, and spend my days hunched over the delicate eggs, painstakingly fashioning each egg into a work of art. Each year I try a new technique or style, searching for design inspirations that surpass the creations of the year before. Some of the eggs take several hours, depending on the tradition in which they are designed. Decorating eggs this way for Easter is a family and ethnic tradition. I have been decorating since childhood, and over the years I have amassed a collection of my favorite ones. Many of the eggs are given as gifts. For the past decade, I have taken photos of them and shared them with the Lithuanian community.

These photos are now published in my new book Eggstraordinary Art: Beautiful Eastern European Eggs for Easter. It is available now worldwide on Amazon.

Click here to go to the sales website.

The eggs in this photo are decorated in traditional Lithuanian style using the drop-pull method. But I have also learned the Ukrainian method, which is far more intricate. The book includes descriptions of these traditions and a photo gallery.

Understanding Openness to Change among Lithuanian Generations

VALUEHOST is a three-year research project funded by the Lithuanian Research Council. We explore changing Lithuanian values, with a focus on emigrants and their experiences in their host countries. In this post, I introduce some interesting findings from one of our studies on changing values at home.

We have analyzed data between the years 2010-2020, from the European Social Survey database on individuals’ values. In this study, we were interested in exploring whether values can change in the short term. Scholars have long held that values are enduring, and that they are very slow to change. In societies, this change would be steady, and progressive over generations. Typically, we notice these differences by comparing our own values with those of our parents’ generation.

But much of the research on values change has been in the context of relatively stable advanced economies. Generations here have labels which we all know: Baby Boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, etc. Societies in the former USSR, though, have had different social, political, and economic transformations. Their process of modernization has been quite different.

In our study, we distinguish between generations which we link to political eras. People who grew up in these different eras in Lithuania acquired their values during vastly different historical periods. Some periods were more turbulent than others. We label them the Stalin generation for individuals born before 1945. The Soviet generation includes those born between 1945 and 1969. The late Soviet generation comprises those born from 1970 to 1989. The Independent EU generation includes individuals born after 1989. One of our aims was to compare the values of these different political generations to one another and over time.

Here we look at one of the results on Openness to Change values, derived from the work of Shalom Schwartz. This is a measure that combines three personal values: self-direction, stimulation and hedonism. Self-direction encompasses the extent to which individuals value independence in thought and action. Stimulation reflects how much people value excitement, novelty and challenges in life. And hedonism refers to the pursuit of personal pleasure or immediate gratification.

We compared six rounds of surveys across more than 11,000 individuals, starting in 2010, and every two years thereafter.

In the figure, we can see that openness to change appears to fluctuate over the years. Some generations are quite similar, but one stands out – the Independent EU generation. These are individuals, who, at the time of the survey, were between the ages of 18 and 30. For the other generations, openness to change declines slightly but increases over time by survey round 10 in 2020. We see the opposite in the youngest generation. Here, openness to change declines steadily over the years. In the final survey round, there is a slight increase. But overall, openness to change has declined for this generation during the 10 years up to 2020.

We would be interested in hearing your thoughts about why this has happened.

Narcissistic CEOs: Strategies for Entrepreneurial Success

Our latest article has just been published in the International Small Business Journal. Have you ever worked with someone who is at times charismatic and charming and at other times nitpicky, controlling and lacking in empathy? A coworker or manager who likes to brag about themselves, their achievements, successes and ambitions to be the best of the best, yet is also often insecure, envious, and manipulative? They instigate office drama and act as the center of attention. They crave glory. They are difficult to work with yet have their superiors, clients, and partners charmed. That coworker or boss likely has narcissistic tendencies.

Our study focuses on CEOs with these types of personality traits.

We analyze the tendencies of narcissistic CEOs to engage in acquiring, developing, and protecting resources. We examine how these behaviors translate to fulfilling their grandiose entrepreneurial strategies. Essentially, narcissistic CEOs are resource hogs. This helps them weather uncertain times, and when threatened, they are further activated to try (and succeed at their) innovative, proactive, and risky strategies.

“It’s all about resources: Narcissistic CEOs and entrepreneurial orientation during disruptions” by Richa Chugh from the Victoria University of Wellington, Audra I. Mockaitis from Maynooth University, Stephen E. Lanivich, University of Memphis, and Javad E. Nooshabadi, Maynooth University, was published in September, 2024.

The article is FREE to access: https://doi-org.may.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/02662426241269774

We would be interested to hear your thoughts about our publication.

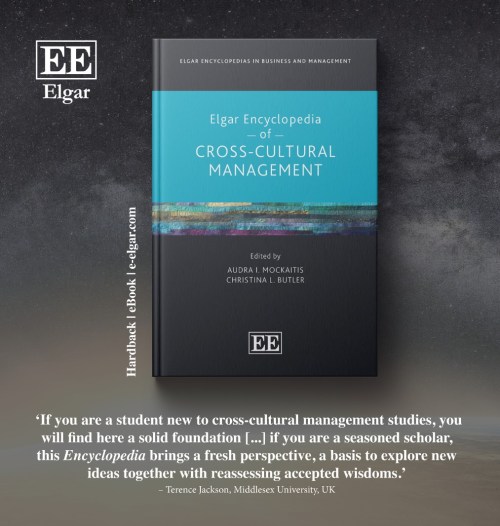

Explore the Elgar Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Management

The Elgar Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Management is available now! Access the first chapter and introductory content for FREE here.

The Elgar Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Management, edited by Professor Audra I. Mockaitis (Maynooth University) and Professor Christina L. Butler (Kingston University), is the first reference book of its kind in the field. The book reflects the eclectic and interdisciplinary nature of cross-cultural management. It includes entries from scholars in cross-cultural psychology, business and management, anthropology, linguistics, sociology, and political science. These contributions form a collective discourse about the evolution and trajectory of the field. Authors present a range of perspectives, theories, and concepts. They challenge traditional paradigms. Together, they offer new multi-paradigmatic explanations to cross-cultural phenomena. Suitable for scholars, students and practitioners, the collection presents the state-of-the art in the cross-cultural management field.

Elgar Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Management Launching in October 2024

The presses are still hot as a new book is coming out in October, 2024. Edited by me and Professor Christina L. Butler from Kingston University, UK, the Elgar Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Management is the first reference book of its kind in the field.

The book reflects the eclectic and interdisciplinary nature of the field of cross-cultural management, with entries from scholars in the cross-cultural psychology, business and management, anthropology, linguistics, sociology, and political science disciplines, contributing to a collective discourse about the evolution and trajectory of the field. Authors present a range of perspectives, theories, and concepts, challenge traditional paradigms, and collectively offer new multi-paradigmatic explanations to cross-cultural phenomena.

Suitable for: scholars from various disciplines, as a guide to new developments in the field; students in any major that has a cross-cultural component to the curriculum (e.g., psychology, management, international business, sociology….) as a useful reference; and anyone with a curiosity about cross-cultural management.

The collection presents the state-of-the art in the cross-cultural management field. Written by eminent scholars from across the globe, entries include summaries, commentaries, and new perspectives on both theory and research. There are 78 chapters, or entries, in eight subject groups:

- Conceptualizations and Components of Culture

- Similarities and Differences across Cultures

- Interacting across Cultures

- Developing Cultural Awareness

- Cultural Identity and Diversity

- The Cross-Cultural Management of People

- Organizational and Institutional Perspectives

- Perspectives on Cross-Cultural Management

Available to purchase on the publisher’s website , AMAZON, Barnes & Noble, and other places!

ISBN: 978 1 80392 817 3

The Palgrave Handbook of Global Migration in International Business

I have recently published a new book.

The Palgrave Handbook of Global Migration in International Business (Audra I. Mockaitis, Ed.) presents novel research on various migration issues in the field of international business. The anthology contains 24 chapters, organized on five key themes representing perspectives and challenges borne by global migration within societies, firms, and individuals. Collectively, the authors examine global migration via the international business lens and present theoretical and practical solutions to a global grand challenge that is rapidly increasing in importance.

The five key themes of the book are:

Theme I: Migration Landscapes in International Business

Theme II: Navigating the Terrain of Language and Culture

Theme III: Leveraging and Managing Migration in the International Firm

Theme IV: Migrants as an International Business Resource

Theme V: The Migrant’s Journey

The book is written for a wide audience;. Researchers, scholars, international business professionals, policymakers, government organizations and NGOs working with migrants (refugees, skilled and unskilled immigrants) or migration issues, students and readers with a general interest in global migration-related topics will find something of interest in the book. The 59 authors are all experts in their fields and all conduct research on migration issues. Notably, while the authors reside in and represent various institutions in twelve countries, many of them are migrants themselves and have first-hand experience of many of the issues presented in the book.

See the Publisher page for more information and to download free sample chapters.

Interested in this book? Available to buy on:

The Book is available in Hardcover (ISBN : 978-3-031-38885-9), Softcover (ISBN: 978-3-031-38888-0) and eBook (ISBN: 978-3-031-38886-6).

VALUEHOST

An invitation to take part in a research study.

We are conducting a 3-year research study on Lithuanian values. We are interested in Lithuanians who have emigrated from Lithuania and are currently living in another country. We would like to learn whether living in another country shapes individuals’ personal values and in what ways. We are interested in the factors that shape our values. Importantly, do individual values change as a result of living in a new country? How long does this process take? Are the values of Lithuanians living abroad different from nonmigrant Lithuanians?

Have you emigrated from Lithuania?

Do you permanently live in any of the following countries?

✔ USA ✔ UK ✔ IRELAND ✔NORWAY ✔ GERMANY

Then we are interested in your experiences. Please click to take the survey.

This project is funded by the Lithuanian Research Council.

Read some of our previously published papers on migrant values.

Our paper on Lithuanian migrants and values has found a relationship between values and intentions to emigrate.

We have also analyzed the values of members of the Lithuanian diaspora. We found both similarities and differences in values between foreign-born Lithuanians and both Lithuanian emigrants and nonmigrant Lithuanians. Read the paper.

The Research Team:

Prof. Audra Mockaitis (PI), Prof. Vilmantė Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė, KTU , Dr Vilmantė Liubinienė, Dr Jurga Duobienė, Dr Ineta Žičkutė, Irma Banevičienė

Coping during the Pandemic: What a Difference a Generation Makes!

Audra I. Mockaitis (School of Business, Maynooth University)

Christina L. Butler (Kingston University Business School)

We present results from the first of a multi-part study that aims to gauge the extent that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused disruptions to people’s work-related and general wellbeing, and whether individuals with certain characteristics are better able to cope with these disruptions. We examine whether different generations are experiencing and dealing with effects of the COVID-19 pandemic differently.

In this note, we first discuss the changing nature of work before turning to highlight the generational challenges inherent in global leadership roles. We then present an overview of our research together with initial findings. We close with our thoughts on what these findings mean for organizations as they move forward into the “new normal”.

COVID has accelerated recent organizational changes

Over recent years, as organizations have tried to keep up with the rapid pace of technological change, they have been implementing flatter structures, more flexibility, and more participatory styles. Thus, pre-COVID, organizations were already emerging that are more fluid, and even boundaryless or borderless and are team- or networked-based [22] [18]. Telework and virtual participation were emerging too in tandem with these structural changes. The COVID-19 pandemic has thrust these shifts to the fore overnight for many other organizations around the globe. Owing to the pandemic, electronic forms of interaction at work have taken over as the only form for many and we expect them to remain the norm for the duration of the pandemic with long-lasting consequences for the future of work. For example, the UK Office for National Statistics is reporting that 44% of the labor force is working remotely during the pandemic, whereas in the same period in 2019 only 12% were doing so.

These changes to organizations and to the organization of work appear to bring many benefits to organizations. They can respond to crises or issues arising with little notice (such as the pandemic) and involving multiple locations, saving them time and costs, enhancing organizational innovation, creativity, diversity and social capital, and enabling them to quickly spread knowledge and access to key stakeholders across the globe, to name a few benefits [22].

However, flexibility is a double-edged sword. It is employees who implement and experience new ways of working. Individuals need to interact with and deal with multiple members across many different types of boundaries, focusing on their internal tasks, but also on maintaining and managing relationships with stakeholders around the globe. Increasing flexibility, although seen as beneficial to organizations, has potentially disruptive consequences for employees (e.g., longer working hours and an increase in crosscutting roles including across the home-work divide). Indeed, pre-COVID, the World Health Organization had declared stress as a 21st century health epidemic resulting in many chronic physical and mental diseases. It is important, though, to take a more nuanced approach to understanding the consequences that may vary by type of employee including the generation of which they are a part.

Pre-COVID, the generational makeup of the global workforce highlighted challenges for Millennials in management roles

As the Millennial generation – the largest generation in modern history to enter the workforce – is now moving into and up the ranks of middle management, it is key to understanding employees’ experiences of work under COVID [14] [17]. According to Hershatter and Epstein [8], Millennials crave stability, structure and clarity in the workplace, factors that are generated by centralized decision-making, well-defined responsibilities, and significant management oversight and that are found in traditional hierarchical organizations. Millennials also demand work–life balance – including flexible working hours and instant gratification – unlike work-centric Baby Boomers. These requirements have led to difficulties in retaining Millennials [1] [8] [14]. Apart from the possibility of increased flexibility offered by the sudden move to significantly more remote working under COVID, other Millennial work requirements may be harder to meet.

Given what we know about Millennials in the workplace, would Millennials find it more difficult to cope with isolation and work during the pandemic?

What our research shows

We received 422 responses to an online survey sent during the months of April and May, on work-related issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. After omitting invalid responses, our final sample was N=325, representing 41 countries, with 65.4% from Anglo countries and 34.6% from non-Anglo countries. 61% of respondents were female and 39% male, 76% were employed full-time, and all but 12% had a formal university qualification. In terms of age, the mean age of our sample was 45.9 years (min=20, max =74). We divided the sample into three groups to represent three distinct generations as follows: the Millennial generation (N=107) included people aged 24 to 40, Generation X (N=133) included ages from 41 to 55, and the Boomer generation (N=85) – from 56 to 74.

In the first part of this study, we included questions about one’s working life in general, as well as reactions to events over the previous week in terms of general wellbeing and stress. Support from Colleagues (α=.71) and Supervisor (α=.86), pertained to how often help and support, listening to problems and encouragement are offered by colleagues and supervisor. Oldenberg’s inventory [6] measured Burnout (α=.88). These constructs measured respondents’ situations pre-COVID.

The remaining constructs measured the extent of disruption caused during the pandemic. Three items gauged the extent to which respondents rated disruptions by COVID to their work, family and personal routines (α=.67). Vitality (α=.78) measured energy levels during the past week. General stress (α=.77) measured the extent of nervousness and negative mood, Cognitive stress (α=.77) measured difficulties in focus and concentration, and Wellbeing (α=.84) measured general feelings of good health, satisfaction and sense of purpose.

Table 1 presents the results of an ANOVA of differences in responses between generations prior to and during the pandemic. The greatest differences in coping during the COVID-19 pandemic are between the Millennial and Boomer generations. Specifically, Boomers report higher levels of vitality and wellbeing and lower levels of general and cognitive stress during the pandemic, as well as overall lower levels of burnout under usual circumstances. This is despite also reporting lower usual levels of supervisor support. Millennials report more or less the opposite. During the pandemic, Millennials experience significantly lower levels of vitality than other generations and significantly lower levels of wellbeing than Boomers. Despite usually perceiving significantly higher levels of supervisor support at work than Generation X, Millennials still experience high levels of burnout (significantly higher than Boomers). During the pandemic, Millennials report greater overall stress and cognitive stress (significantly higher than the other generation groups).

Why are there such stark differences among the generations? Why are the Millennials struggling more under COVID?

Butler, Zander, Mockaitis, and Sutton [4] suggest that global leaders who are successful in their roles have developed the necessary focus, drive and people-orientation [10] to confront changing organizational structures and the changing nature of work itself by practicing three interrelated roles: boundary spanner, blender and bridge maker. At the same time, these authors argue that Millennials from around the world may struggle comparatively more than other generations as they move toward or take up management positions. Our findings seem to reflect this analysis.

Organizational boundary spanners create and maintain strong linkages with the external environment to enable information and resources to flow across boundaries and to exert influence on stakeholders in achieving organizational objectives [13]. A desire for “quick” information and a focus on self may lead Millennials to struggle to present business needs in a sufficiently robust manner [5] to engage business audiences across a boundary-spanning environment [2][13][19] compared with other generations, especially when their own line managers are fully immersed in the current crisis and so less available to support direct reports.

Butler et al. [4] suggest that a blender role is important to achieve cultural fusion [12] among team members resulting in the group and the individual being equally, but differently, valued [9][11]. Despite being digital natives [16][20], narcissistic tendencies may interfere with a fully blended team experience for Millennials, especially when all work is conducted virtually, as can be the case during the pandemic, and when line managers are less available. This can lead to a negative impact on stress levels and well-being.

Lastly, successful bridge makers engage readily with the ‘cultural other’ while ensuring successful interaction among people across different national cultural boundaries [15]. DiStefano and Maznevski [7] emphasize the importance of being able to decenter, a challenge for Millennials who are comparatively self-focused. A highly virtual work environment exacerbates the lack of interest in others and increases a focus on self [21], interfering with the ability to see others’ perspectives.

It is thus paradoxical that Millennials, who are characterized by being technologically savvy, are having the hardest time coping with the pandemic. All of our respondents reported similar degrees of disruption to their lives as a result of COVID. Members of other generations appear to be getting on with their lives better than Millennials, despite having relatively more responsibility (e.g., balancing work and family or supervisory roles). They report higher levels of wellbeing and less stress. However, our research suggests that in comparison to other generations, Millennials may need more attention from supervisors (in the form of support and encouragement), who are less available now. Organizations need to respond to this leadership paradox now to move successfully from COVID to the “new normal”.

You can read a more detailed report from this study here.

Please cite this paper as:

Mockaitis, A.I. & Butler, C.L. (2023). Disrupted: remote work and life under lockdown during the great COVID-19 pause. MUSSI Working Paper No 17. MUSSI, Maynooth, Ireland.

References

- Anderson, H.J., Baur, J.E., Griffith, J.A., and Buckley, M.R. (2017), ‘What works for you may not work for (Gen) Me: Limitations of present leadership theories for the new generation’, Leadership Quarterly, 28(1): 245–60.

- Barner-Rasmussen, W., Ehrnrooth, M., Koveshnikov, A., and Mäkelä, K. (2014), ‘Cultural and language skills as resources for boundary spanning within the MNC’, Journal of International Business Studies, 45(7): 886–905.

- Butler, C.L., Sutton, C., Mockaitis, A.I. and Zander, L. (2020), ‘The new millennial global leaders: what a difference a generation makes!’ In: Zander, Lena, (ed.) Research handbook of global leadership: making a difference. Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. pp. 141-163.

- Butler, C.L., Zander, L., Mockaitis, A.I., and Sutton, C. (2012), ‘The global leader as boundary spanner, bridge maker, and blender’, Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 5: 246–9.

- Carr, N. (2008), The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google. New York: Norton.

- Demerouti, E., Mostert, K., and Bakker, A.B. (2010), ‘Burnout and work engagement: A thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs’, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15 (3): 209-222.

- DiStefano, J.J., and Maznevski, M.L. (2000), ‘Creating value with diverse teams in global management’, Organizational Dynamics, 29(1), 45–63.

- Hershatter A. and Epstein, M. (2010), ‘Millennials and the world of work: An organization and management perspective’, Journal of Business Psychology, 25: 211–23.

- Hewstone, M. and Brown, R. (1986), ‘Contact is not enough: An intergroup perspective’. In M. Hewstone, and R. Brown (Eds), Contact and Conflict in Intergroup Encounters. Oxford: Blackwell, 1–44.

- Holt, K. and Seki, K. (2012), ‘Global leadership: A developmental shift for everyone’, Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 5(2): 196–215.

- Hornsey, M. and Hogg, M. (2000), ‘Assimilation and diversity: An integrative model of subgroup relations’, Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4: 143–56.

- Janssens, M. and Brett, J.M. (2006), ‘Cultural intelligence in global teams: A fusion model of collaboration’, Group and Organization Management, 31(1): 124–53.

- Johnson, K.L. and Duxbury, L. (2010), ‘The view from the field: A case study of the expatriate boundary-spanning role’, Journal of World Business, 45: 29–40.

- Kwoh, K.L. (2012), ‘More firms bow to generation Y’s demands’, Wall Street Journal, 22 August: B6.

- Levy, O., Lee, H.J., Jonsen, K., and Peiperl, M.A. (2019), ‘Transcultural brokerage: The role of cosmopolitans in bridging structural and cultural holes’, Journal of Management, 45(2): 417–50.

- Palfrey, J. and Gasser, U. (2008), Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books.

- Pew Research Center (2018), ‘Millennials surpass Gen Xers as the largest generation in US labor force’, at www.pewresearch.org (accessed 10 July 2019).

- Simões, V.C., Da Rocha, A., De Mello, R.C., and Carneiro, J. (2015), ‘Black swans or an emerging type of firm? The case of borderless firms’, The Future of Global Organizing: Progress in International Business Research, Vol. 10: 179-200.

- Small, G. and Vorgan, G. (2008), iBrain: Surviving the Technological Alteration of the Modern Mind. New York: Harper Collins.

- Tapscott, D. (2009), Grown Up Digital. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Weber, J. (2017), ‘Discovering the Millennials’ personal values orientation: A comparison to two managerial populations’, Journal of Business Ethics, 143(3), 517–29.

- Zander, L., Butler, C.L., Mockaitis, A.I., Herbert, K., Lauring, J., Mäkelä, K., Paunova, M., Umans, T. and Zettinig, P. (2015), ‘Team-based global organizations: the future of global organizing’, In: Van Tulder, R., Verbeke, A. and Drogendijk, R., (eds.) The future of global organizing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. pp. 227-243. (Progress in International Business Research).

Making a difference through global leadership

I am pleased to be a part of a recently published book, the Research Handbook of Global Leadership: Making a Difference (Lena Zander, Ed.). The book’s publication is timely, as leadership in these uncertain times becomes ever more important. Many international organizations are and will be facing numerous challenges and will need to develop new strategies, skills and ways to overcome them. More than ever before true leadership will need to include skills to navigate an uncertain landscape, while simultaneously demonstrating compassion, inclusivity, social consciousness, and responsibility across an even greater number of boundaries and contexts.

I have contributed to three chapters in this book. In Chapter 4, Action intent: Getting closer to leadership behavior in 22 countries, 23 authors examine how leaders make the choices they do in a study of 1,868 leaders worldwide. In Chapter 9, The new Millennial global leaders: What a difference a generation makes!, Butler, Sutton, Mockaitis and Zander examine inter-generational workplace relations, the characteristics of millennial generation employees and the future of work and global leadership facing this generation. In Chapter 24, A world of learning: The future of management education based on academia and practitioner universitas, Zettinig, Zander, Zander and Mockaitis discuss the future of management education, especially the way current and future leaders are “trained” to acquire standardized skill sets and offer some ideas for enhancing the relevance of leadership learning.

All of the book’s 25 chapters, by renowned scholars in the field, add to the global leadership domain by offering novel insights into “making a difference.”

A Portrait of Lithuanian Societal Values

Notes: ESS = European Social Survey; Hof = Hofstede cultural dimensions; SVS = Schwartz Values Survey; WHR = World Happiness Report; WVS = World Values Survey.

The values emphasized by a society are central to understanding its culture; they lie at the very heart of culture and shape the society’s beliefs, understanding, practices, norms and institutions (Schwartz, 2006). To me culture is a set of learned and shared values that influences our way of life, our perceptions, beliefs and attitudes, and distinguishes one human group from another (Mockaitis, 2002).

The figure above represents a glimpse into Lithuanian culture, based on an analysis of large-scale studies of values to date that have included Lithuania. There are five such studies that have ranked countries based on values or combinations of values at the societal level:

- A study in 50 societies conducted by Ralston et al. (2011) based on the Schwartz Values Study (SVS).

- A study on Lithuanian national cultural values conducted by Mockaitis (2002) that compares Lithuania to 69 other countries in Hofstede’s database.

- The World Values (WVS) by Inglehart et al. (2014) that provides access to a 70-country database.

- The World Happiness Report (WHR) by Helliwell et al. (2018) of 156 countries.

- The European Social Survey (2016) (ESS) comparing values in 23 European societies.

These studies enable us to discuss Lithuanian values relative to those of other countries/cultures albeit not in absolute terms. The focus is on the dimensions of values in the main circle. The larger the slice of the circle, the more emphasis is placed on the values comprising that dimension by Lithuanians. The outer layer depicts the types of values that comprise each of the dimensions, with additional supporting evidence about Lithuania’s ranking on related single-item values from other studies. In depicting the cultural orientations, I have followed the structure of Schwartz (2006); the cultural value orientations are displayed based on shared assumptions between them. Adjacent orientations share assumptions and are compatible. Incompatible orientations or those with opposing assumptions lie on opposite sides of the circle. A brief explanation of the orientations/dimensions follows.

Schwartz’s (2006) first dimension is labelled autonomy vs embeddedness. This is conceptually similar to individualism vs collectivism, and thus the orientation affective autonomy and individualism are adjacent, while embeddedness is opposite. In individualistic cultures people place emphasis on the self over the group and are encouraged to express their own ideas, speak their mind and rely on oneself. Affective autonomy encourages individuals to pursue personal gratification, pleasure, excitement and variety in life. We see that Lithuania is a mildly individualistic society (ranking 28th out of 70 countries) and quite low on affective autonomy. Lithuanians value independence and self-reliance to a moderate degree but not personal fulfilment and personal enjoyment. This is supported by Lithuania’s low ranking in the ESS at 19th of 23 countries. In affective autonomy Lithuania is similar to India, Chile, Lebanon and Thailand.

However, Lithuania scores rather high on the opposing orientation Embeddedness. Embedded cultures believe that people are interwoven within the wider collective. Relationships are important as a means for attaining shared goals and maintaining a shared identity. Restraining from actions that might disrupt the societal order, stability and security is the norm, as is respect for tradition and the status quo. In the WHR and WVS, Lithuania ranks rather low on the belief that people are able to make their own life choices. People are bound by or embedded within the wider group or society. Lithuania’s embeddedness orientation is similar to that of Singapore, Finland, Turkey, Hong Kong and Malaysia.

Related to this is the uncertainty avoidance dimension of Hofstede (1980a). This dimension depicts “the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by uncertain or unknown situations (Hofstede, 1991: 113)” and their ways of coping with uncertainty. In societies higher on this dimension we find lower tolerance of change, more coping mechanisms such as rules, procedures, control and details, higher stress, emotions and anxiety, and a lower acceptance of outsiders. Lithuania ranks medium high on this dimension, similar to Germany, Equador, Thailand and Morocco. Easy going or laid back would not be fitting adjectives for describing Lithuanians.

How concerned are Lithuanians with the welfare of others? The value orientation egalitarianism underscores concern for other people’s welfare, recognizing them as equals, and an expectation to act for the benefit of others (Schwartz, 2006). Values held by egalitarian cultures are equality, honesty, social justice, being helpful and dependable. Lithuanian’s ranking is not high (35th of 50 countries), on par with countries such as China, India, South Korea, Hong Kong and Vietnam. Supporting evidence from the ESS shows that compared to other European countries, Lithuanians strongly believe that men have more rights to a job than women, and strongly disbelieve that all people should be treated fairly and that people should care about the wellbeing of others (ranking last out of 23 European countries).

In the WVS Lithuania scores high on survival values and low on self-expression values. Inglehart and Welzel’s (2005) survival vs. self-expression values were conceptually refined by Welzel (2013) to produce the emancipative values index. Emancipative values are akin to human empowerment and place priority on gender equality, equal opportunities, freedom of choice, personal autonomy and self-expression, acceptance of homosexuality, abortion and divorce. Lithuania scores rather low on emancipative values. According to Welzel (2013), emancipative values strengthen with rising levels of education and resources such as wealth and intellectual skills. Opportunities to connect with others also induce these values. As emancipative values spread through society, people also become less preoccupied with material security and shift their focus to happiness and life satisfaction (Bates, 2014). As Lithuania’s position on mastery and material wealth shows, this is not yet the case; Lithuanians are also relatively unhappy, ranking 50th (of 156 countries) on the WHR and 22nd (of 23 countries) on the ESS.

In the WVS Lithuania scores high on secular-rational values and low on traditional values. This dimension was further refined by Welzel (2013) into the secular values index. Lithuania scores intermediate on secular values (ranking 22nd out of 71 countries), placing relatively low priority on authority, including religious authority (faith, commitment, religious practice), patrimonial authority (the nation, the state and parents), authoritative institutions, such as the army, police and the justice system, and normative authority (anti-bribery, anti-cheating and anti-evasion norms). In fact, in perceptions of corruption, Lithuania ranks 4th of 156 countries in the WHR by Helliwell et al. (2018).

In the figure adjacent to secular values and opposite egalitarianism we find power distance. This dimension from Hofstede (1980a, 2001) reflects the extent to which less powerful people within a society accept the fact that power is distributed unequally within the society, institutions and organizations. With an index score of 45 and a ranking of 51 out of 70 countries, Lithuania is in the medium range on power distance, as are countries such as Hungary, Jamaica, USA and Estonia. In certain contexts displays of authority, status, power, prestige and inequality will be acceptable, in others less so, although the values associated with uncertainty avoidance, low egalitarianism and embeddedness may connote that power and inequality are part of the fabric of order in society and people are socialized to accept the rules and obligations embedded within the hierarchical structure. As such there may be little outward resistance despite a lower internal tolerance or preference for power distance.

On opposing poles in the figure we see harmony and mastery. Lithuania ranks high on mastery and lower on harmony. The lower ranking on harmony is associated with a lower importance on and appreciation for the natural environment (India, Portugal, Taiwan and Russia rank similarly). Mastery embodies values such as self-assertion, recognition, success and competence, control over the environment or changing it for the purpose of attaining one’s own goals (Schwartz, 2006). Next to mastery is the masculinity dimension of Hofstede (1980a), which pertains to the “extent to which the dominant values in society are ‘masculine’” (Hofstede, 1980b: 46); masculine values are those such as assertiveness, the attainment of wealth, money and things, ambition and success. On the opposing pole are feminine values, such as nurturing, cooperation, relationships, friendliness, quality of life and harmony. Lithuania ranks high on masculinity (14th out of 70 countries, similar to China, Philippines, Colombia and Poland) and high on mastery (ranked 12th of 50 countries, near Bulgaria, Portugal, Turkey and Russia). ESS results support Lithuania’s high ranking on mastery and masculinity; out of 23 European countries Lithuania ranks first in the importance placed on material wealth and fourth in the extent to which success is valued. With respect to caring for the environment and preserving nature (harmony), Lithuania ranks 21st of the 23 European countries on the ESS.

References

Bates, W. (2014). Where are emancipative values taking us? Policy, 30 (2): 12-21.

European Social Survey (2016). ESS8-2016 Documentation Report. Edition 2.0. Bergen, European Social Survey Data Archive, NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data for ESS ERIC.

Helliwell, J.F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J.D. (2018). World Happiness Report 2018. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Hofstede, G. (1980a). Culture’s Consequences. International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1980b). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9: 42-63.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin & B. Puranen et al. (eds.) (2014). World Values Survey: Round Three – Country-Pooled Datafile Version: www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV3.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

Inglehart, R. & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mockaitis, A.I. (2002). The influence of national cultural values on management attitudes: A comparative study across three countries. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Vilnius University.

Ralston, D.A., Egri, C.P., Mockaitis, A.I., et al. (2011). A twenty-first century assessment of values across the global workforce. Journal of Business Ethics, 104: 1-31.

Schwartz, S. H. (2006). A theory of cultural value orientations: Explication and applications. Comparative Sociology, 5 (2-3): 137-182.

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

World Values Survey. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org